by David Wyn Jones

It could be a question in a pointless TV quiz: which Beethoven symphony was the most frequently performed in Vienna in his lifetime; was it a) the Eroica, b) the Fifth, or c) the Ninth? In fact, it was none of these. The most frequently performed symphony was the Seventh Symphony. Composed in 1811-12, it lay unperformed for the best part of two years until it was included in a charity concert in December 1813 to raise money for Austrian and Bavarian soldiers injured in the Battle of Hanau, part of the final push that led to Napoleon’s defeat. The symphony had never been conceived as a battle symphony but by association with another work that was performed in the same concert, Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory (the so-called Battle Symphony), it quickly became associated with sentiments of national endeavour and celebration. It was repeatedly performed to great public acclaim in Vienna over the next couple of years and retained that popularity, perhaps the nature of the popularity too, right through to the end of Beethoven’s life.

Early performances would have used manuscript parts prepared by professional copyists and owned by Beethoven. The work was first published in 1816 by a new and very enterprising firm in Vienna, Steiner. His ambition, like the Seventh Symphony itself, captured the optimism of the time. Not only was the work distributed via a network of associated publishers throughout German-speaking Europe (Augsburg, Berlin, Bonn, Hamburg, Frankfurt etc. etc.) but was issued in several formats. In additional to the usual orchestral parts, Steiner offered a full score (an indication of emerging conducting practice), and arrangements for string quintet, piano trio, piano duet, piano solo and what was advertised as ‘Harmonie für 9 Stimmen’, that is a wind band of nine instruments, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns and contrabassoon. As with string versions and the piano versions, Steiner was obviously confident that the Harmonie version would sell.

In a rarefied way that has always elevated the composer and his work above commercial practice, Beethoven scholarship has put these arrangements to one side: they add nothing to our understanding of the Seventh Symphony is the routine outlook. But this ignores the fundamental point that many people in Beethoven’s Vienna would have understood the symphony as a work for Harmonie, and to dismiss that experience is to circumscribe Beethoven’s reputation at the time. Scholarship has also routinely asked the question: are these arrangements authentic? There is no evidence either way, beyond the fact that Beethoven certainly knew about them. Musically, it is easy to point to aspects of the Harmonie version that do not seem to fit with what we deem to be good Beethovenian practice, most obviously that the work is transposed down a tone to G major except for the scherzo which remains in the original key of F, producing an overall key pattern not found in any authentic work by the composer. But, remembering our curiosity about the Beethoven experience in his own environment, this is an inappropriate question to pursue. Much more productive would be to understand the place of Harmoniemusik in music making of the time.

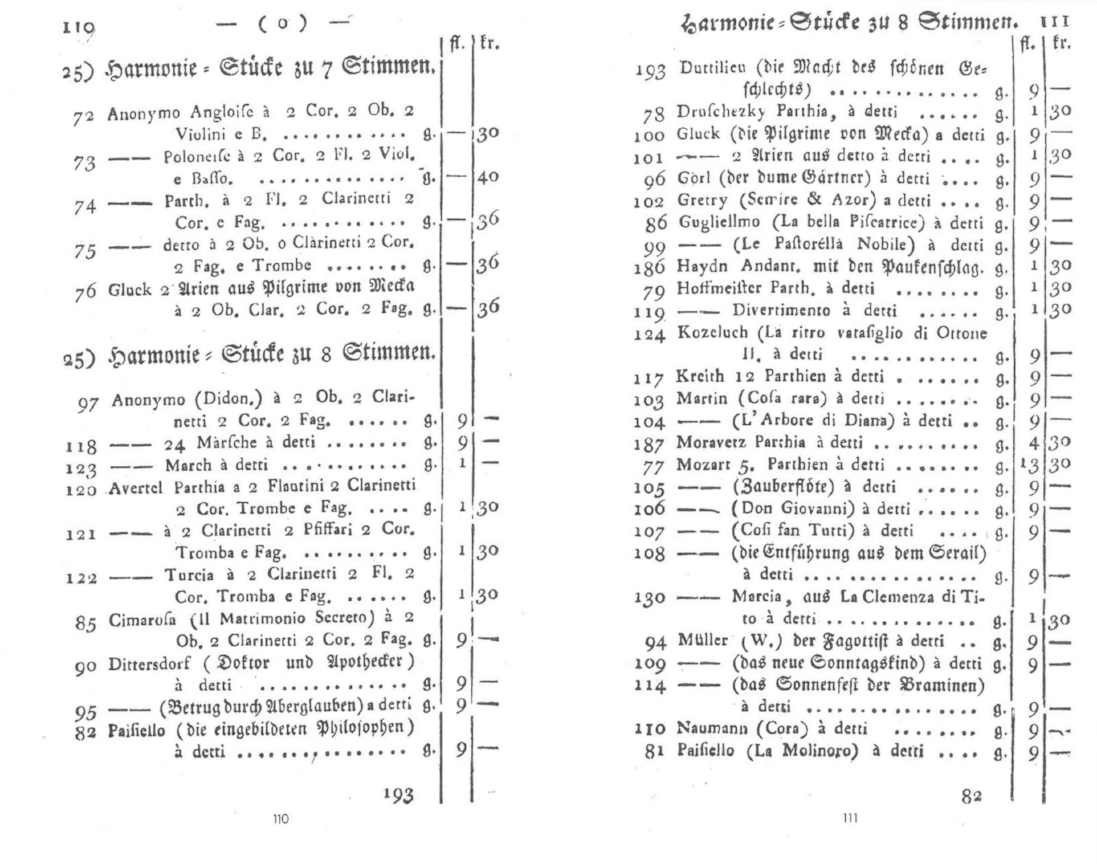

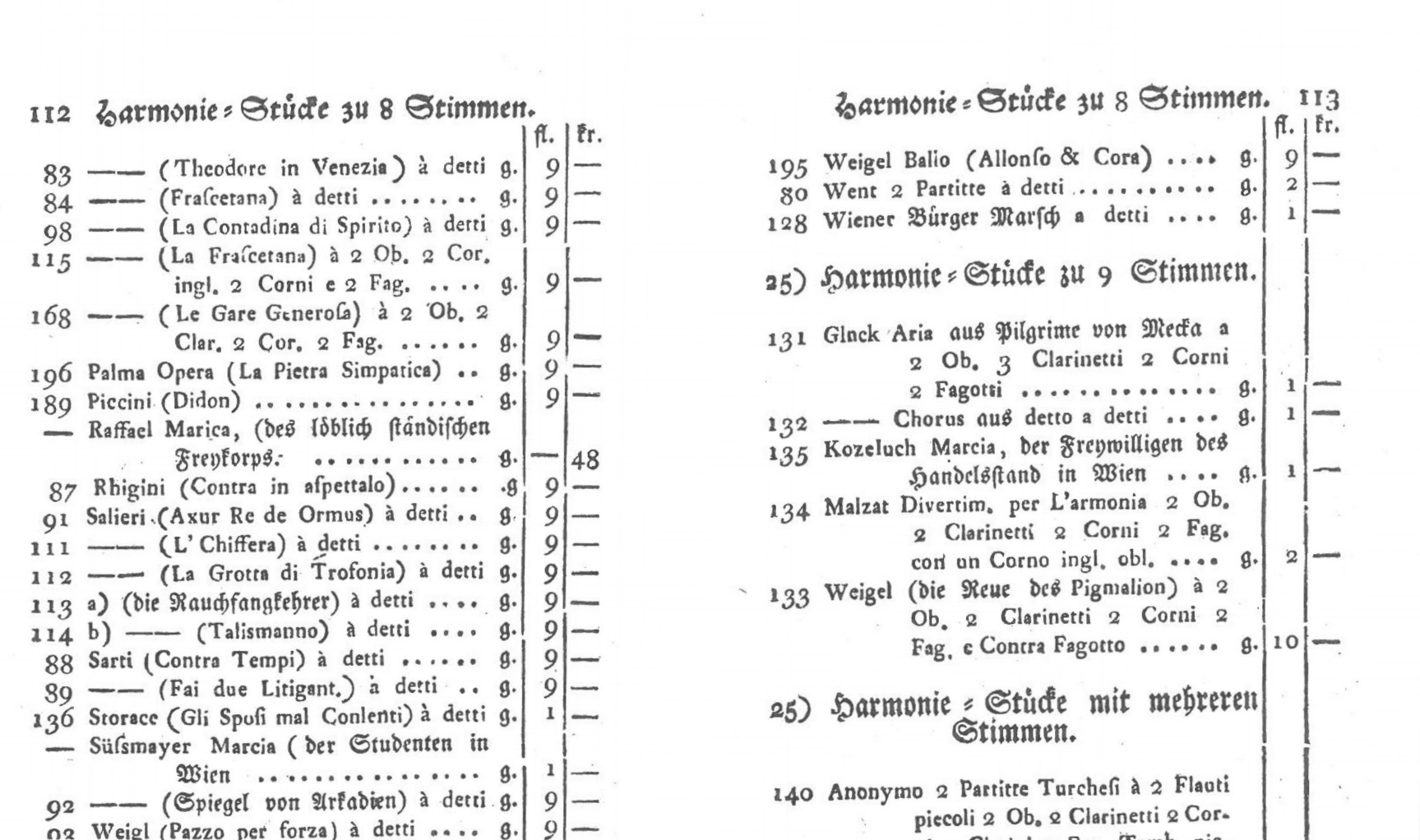

The illustration reproduces four columns from a catalogue of music that could be purchased from the shop of the music dealer Johann Traeg in 1799. This catalogue lists close to 14,000 items of all kinds, including over 180 works for Harmonie, wind-band forces ranging from two instruments to ten or more. In the top right-hand column there are several entries for Mozart: five original works for Harmonie that could be purchased as a package for 13 gulden and 30 kreutzer, and five arrangements of music from Così fan tutte, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Don Giovanni, La clemenza di Tito and Zauberflöte. Further up there is an arrangement of the slow movement from Haydn’s ‘Surprise’ symphony. Arrangements of orchestral works, especially opera overtures but also complete symphonies, were common, and formed part of a repertoire that was in constant demand. From the middle of the eighteenth century onwards there had been a distinct trend in Austrian music making of patrons employing wind bands rather than orchestras, partly a matter of finance (a standard Harmonie of eight cost much less than an orchestra), partly a matter of fashion too.

The sound of Harmoniemusik became ingrained in the musical imagination, to the extent that composers sometimes evoked it in other works. In Act 2 of Così fan tutte the two lovers, Ferrando and Guglielmo, woo the increasingly amenable women, Fiordiligi and Dorabella, against the sound of a wind ensemble, a ‘Harmonie zu 6 Stimmen’ to use Traeg’s terminology. In the chorus of praise that concludes Part 2 of Haydn’s oratorio, The Creation, the excitable outer choral sections enclose a luxurious hymn of thanks to the Almighty, ‘To Thee, O Lord, all things look upwards for sustenance’, accompanied by a Harmonie - a divine harmony in this instance - of nine instruments. Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, too, has Harmonie moments in its original orchestral version, most obviously the ‘Harmonie zu 6 Stimmen’ that takes the lead in the trio of the scherzo, the major-key section in the Allegretto, the very opening of the work and, most startlingly, the bleak minor chord that opens the slow movement. Listening to the Harmonie version of this symphony is much more than an antiquarian historical exercise: it opens our ears to new perceptions of the music altogether.

David Wyn Jones is a professor of music at Cardiff University and has written extensively on music in the Classical period. His most recent book, Music in Vienna, 1700, 1800, 1900, was published by Boydell in June 2016.

This guest blog was part of our 2017 project 'The Harmonie in Beethoven's Vienna'. You can hear the Harmonie version of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony and other arrangements from the Steiner Catalogue on our forthcoming CD ‘Beethoven Transformed: vol. 2’: you can read and hear more about the project and how to support it here.