by Emily Worthington

Though there are many fabulous original works for Harmonie from the late-18th and early-19th centuries, Boxwood & Brass spends much of its time playing arrangements. Some are historical arrangements, made by contemporaries of the composer, often within a few months of the original work. Others are new arrangements, made by Robert Percival, our bassoonist and resident Harmoniemusik expert.

Why do we do this? After all, we could spend our time just playing the standards of the Harmoniemusik repertoire – Mozart Serenades, Beethoven's Sextet, Octet and Rondino, Krommer Partitas – or exploring the reams of lesser-known works, by composers such as Druschetzky, Pleyel and Triebensee. It's not easy to sell arrangements, either - they tend to be treated with caution, both by Musicologists and concert promoters. They're often considered a 'surrogate', a pale shadow of the original work, or even disrespectful to the composer's 'original intentions'. So why do we bother?

I know Robert has some convincing reasons for wanting to make new arrangements (something he'll elaborate on in a later post), but I wanted to talk about what I as a player get out of playing this 'unoriginal' repertoire. As you'll see, I think there many things that arrangements can teach us, as players, scholars, and listeners.

Historical Insight

Harmoniemusik was integral to musical culture in Europe, from around the 1770s until the 1830s. As a wind player working in a court where Harmoniemusik was cultivated – as were most of the important players of the period – Harmoniemusik arrangements would be your bread-and-butter repertoire, possibly more than orchestral or chamber music.

As a student of the 18th-century clarinet (which, after over a decade of playing professionally, I still am!) I can honestly say I've learned more about my instrument and historical performance styles through Harmoniemusik than through any other repertoire. And you guessed it, the most valuable training of all has been playing arrangements, particularly for 6-part Harmonie (with no oboes). Opera arrangements in particular have immersed me in the characters, topics and gestures of 18th-century music, elements that I now recognise in any music of the period – and I'm fairly confident that my colleagues share this feeling.

In-depth discussions about how to be Figaro...

Arrangements are also crucial to discovering the technical capabilities of the period instruments that we play in Boxwood & Brass. The demands of Harmoniemusik clarinet parts, particularly in the 6-part arrangements that we often play, vastly outstrip anything seen in symphonic or chamber music of the same period. I have to learn to take on the role of a violin and an operatic Prima Donna, as well as, in the 9-part repertoire, contend with extremely tricky accompanying figuration the like of which I've rarely seen elsewhere. It's taught me a healthy respect for the average 18th-century court clarinettist. It's also made the demands of the early-19th century concerto repertoire by Weber, Spohr, Crusell and Tausch seem much less a technical bolt from the blue, and more of a logical progression from what was already happening. And given that these arrangements were commonly made by the musicians themselves, or by those with a detailed understanding of the instrument, I would argue that these arrangements teach us about the technical level that must have routinely been achieved on Classical-period wind instruments – giving us something to aim for!

Musical Understanding

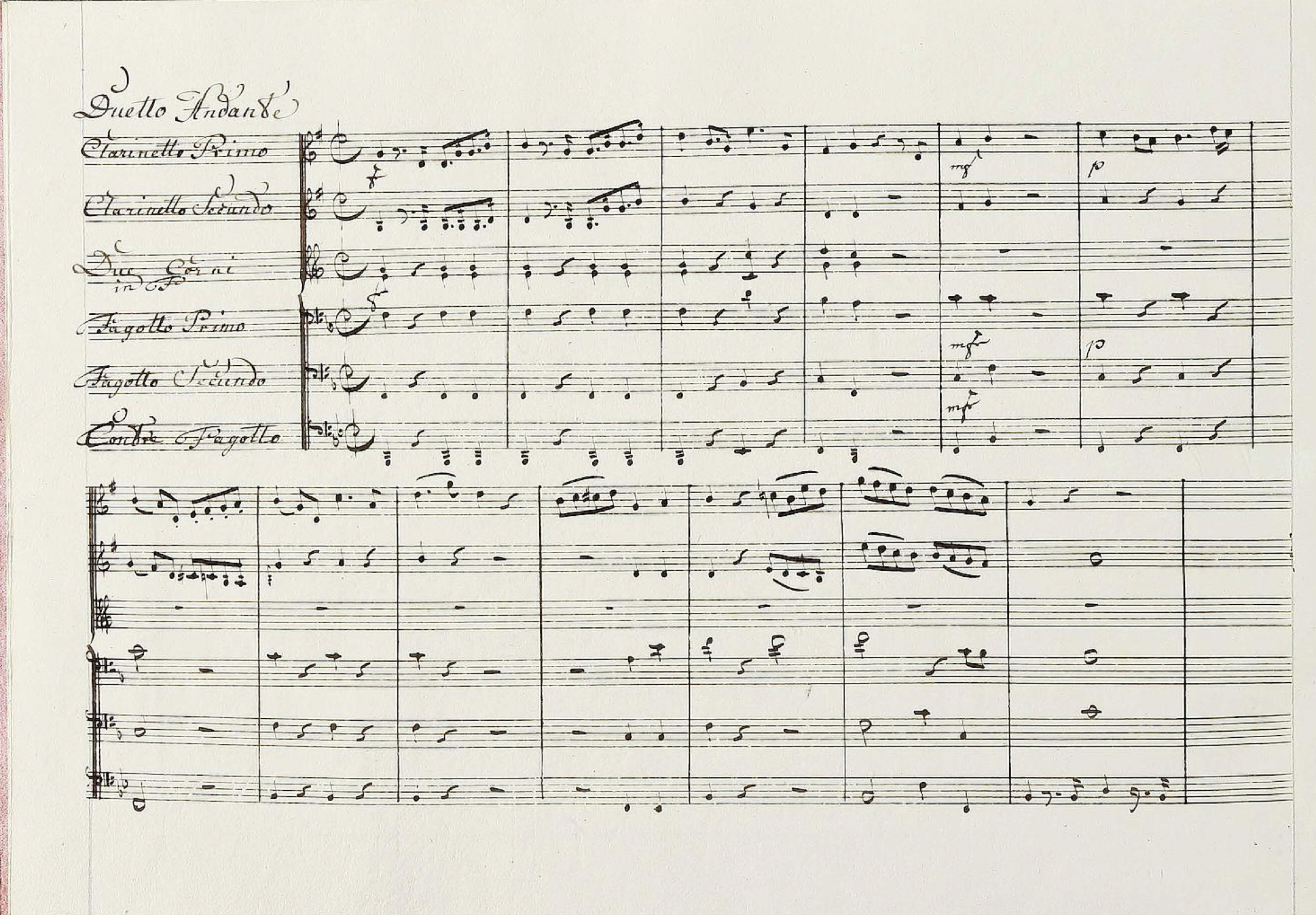

'Come ti piace' from Mozart's La Clemenza di Tito, arranged by Georg Kaspar Sartorius (1754–1809). For the first clarinet, this is an exercise in being tutti, solo and duo voice, and violin commentary all in the space of a few bars. Made available online by the Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Darmstadt.

The second thing I love about playing both historical and new arrangements is the insight I gain into the music itself. I understand familiar pieces from a different perspective by playing lines that the clarinet doesn't get in the original (such as the in Czerny version of the Beethoven Septet Op. 20), and I get to perform music to which I could otherwise only listen (such as Beethoven's 'Pathetique' Piano Sonata). But there's also something about a 6- or 9-part arrangement of an operatic or symphonic work that really condenses and intensifies the harmony and structure. The combination of the reduced number of players and our physical proximity means we can hear much more clearly details of harmony and texture that are diffused in a larger ensemble. In addition, period instruments amplify the contrast between different tonalities by offering open and clear sounds in the home key, and covered and stopped ones whenever things become distant or exotic. Then there's the fact that we play without a conductor, approaching everything as chamber music, meaning that we all develop an intimate knowledge of each other's lines.

As a result, when I finish a project with B&B, I always feel that I've got to know the music from the inside out. This colours my understanding of it in other contexts, something that surely must also have been the case for 18th-century musicians. For instance, my first experience of Mozart's La Clemenza di Tito was in a Harmonie arrangement, meaning that when I played in the orchestra for the opera a few months later, I knew many of the vocal and string lines better than my own!

Taking Control

The final aspect that interests me is also about the relationship between Harmoniemusik and orchestral playing . Most of the arrangements we play are of large-scale works that would normally be conducted, and as I've said, bringing them into the Harmonie means approaching them as chamber music. Now, as an orchestral musician, we have our moments of autonomy, and certainly contribute a great deal to the whole (don't get me started on those reviewers for whom a great performance is always the work of the conductor, and a poor one always the fault of the musicians). And it's true that conductors vary from micro-managers to hands-off facilitators. But ultimately, in an orchestral context, we have to fit everything we do into someone else's vision. There's little room for discussion, or to influence the outcome of interpretative decisions (apart from when I've been lucky enough to join the wonderful Spira Mirabilis – a group who have certainly influenced my approach to many of the issues discussed here).

By contrast, when B&B tackle, let's say, a symphony – be it one of Robert's terrific Mozart arrangements, or an original arrangement such as Beethoven 7 – there's no conductor to tell us what to do. We can shape our own version of the work – and indeed we have to. One of the guiding principles of B&B is to treat Harmoniemusik arrangements on their own terms, not as a poor man's version of the original, primarily because we find this leads to a more convincing result. So we don't try to replicate an orchestral sound, or an orchestral interpretation of symphonic music: we look for something different, something that suits our ensemble. It's the only context I'd risk using the word 'authentic' (so loaded in historical performance circles): whatever we're playing, it becomes authentic Harmoniemusik, and authentically ours.

Boxwood & Brass will be touring 'The Harmonie in Beethoven's Vienna' during February 2017 to venues in Huddersfield, Oxford, London and Cardiff. The programme contains arrangements of the overture to Boieldieu's opera 'Jean de Paris' and Beethoven's 7th Symphony, as well as an original Partita by Triebensee.

Dr Emily Worthington is principal clarinetist and co-director of Boxwood & Brass. She is also Lecturer in Music Performance at the University of Huddersfield. Emily's full biography can be found here.